Invasive Plants, A Threat to Rivers

by Jose Luis Gallego, environmental communicator (@ecogallego)

The presence of invasive plant species in rural areas, both in crop fields and woodlands, constitutes one of the greatest threats to their biodiversity. Numerous voices, from scientific institutions to conversation groups, are warning tirelessly of the global expansion of this phenomenon. Among the areas suffering the most severe environmental impact are fluvial ecosystems.

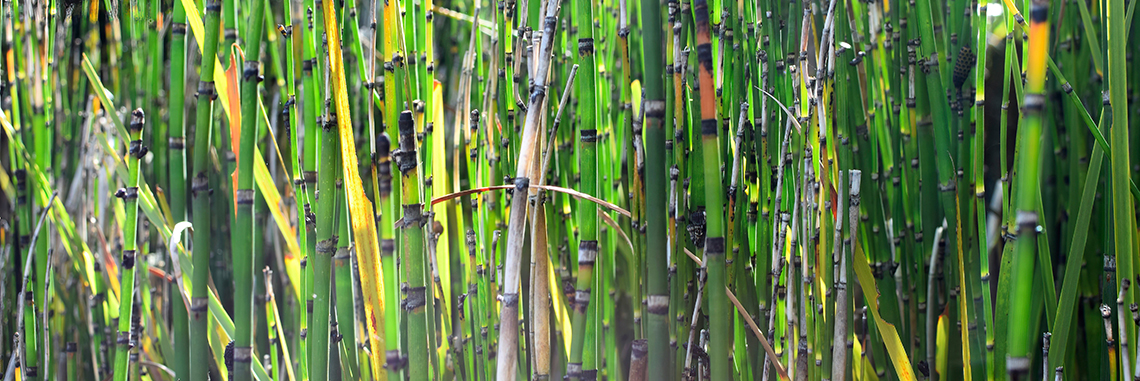

The giant reed or wild cane is one of the exotic invasive plants that is most detrimental to our rivers. Classified under the scientific name Arundo donax, this rhizomic species, thought to be native to Asia, has managed to invade riparian spaces in most parts of the world thanks to its astonishing ability to adapt to all kinds of environments. From the edges of reservoirs and irrigation channels to the most denaturalized urban waterways with the highest levels of pollution, the reedbeds thrive just about everywhere.

This popular invasive species seems to do particularly well in Mediterranean regions where it manages to survive long periods of drought and the most severe heat waves, and summer wildfires actually contribute to its propagation. Whereas wildfires devastate indigenous riparian vegetation, the giant reed not only survives the flames but often grows back even more vigorously after burning.

This extraordinary resilience comes down to the particular characteristics of its rhizome: a genuine wonder of nature that can remain dormant for weeks, even months, at a depth of more than half a metre. After the fire has died down and the plant buds again, the shoot can grow around ten centimetres every day, returning to its height of six metres in a matter of months.

Giant reed

The giant reed did not reach the Iberian Peninsula by accident but was introduced centuries ago to be cultivated as a construction material. Today its exceptional capacity to adapt and survive has led the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to classify the giant reed as one of the planet’s hundred most destructive invasive species.

In Spain, where the giant reed is also included in the Catálogo Nacional de Especies Exóticas, several eradication plans have been implemented. The reasons go beyond the threat the plant poses to biodiversity. Reedbeds also reduce the drainage capacity of rivers and canals, which is detrimental to farming and multiplies the destructive impact of flooding by accumulating and obstructing bridges.

Joining the giant reed as one of the most destructive invasive species to fluvial ecosystems is the common water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes). The plant not only invades the banks but the entire bed, literally burying the river beneath its leaves. One of the most severe cases can be found in the Guadiana River basin.

Giant reed

Running a length of 800 kilometres, the river is the fourth longest and widest on the Iberian Peninsula. The Guadiana cuts through Extremadura, crossing the entire province of Badajoz – this is the stretch where the common water hyacinth has invaded the watercourse. Images of this invasive species engulfing the entire river for kilometres have made their way around the world.

The water hyacinth is a large aquatic plant (its leaves can grow to the size of a palm) originally from South America. In its native habitat, the plant has natural predators and competitors, which keep its expansion in check. The first exemplars appeared floating in the Guadiana in 2004. By now the species has spread along more than 150 kilometres of the river.

The presence of this invasive plant threatens to destroy many of the rich and varied fruit and vegetable crops cultivated on the fertile plain of the Guadiana, including rice, tomatoes, peppers, asparagus, and more. In addition to having a devastating impact on the area’s rural economy, the species has lethal effects on the fluvial ecosystem.

The dense floating layer of water hyacinths covers the river’s surface completely, preventing sunlight from penetrating the water and thereby seriously altering aquatic life. The view from the riverbank is dramatic, revealing how the former watercourse has transformed into a long vegetative corridor, a green path stripped of indigenous flora and fauna, from reeds and bulrushes to kingfishers and otters.

The battle to eradicate this invasive species comes at an enormous financial cost. Over the past decade, more than 30 million euros have been poured into a plethora of initiatives: from floating containment barriers to extraction efforts with heavy machinery. Several tons of this aquatic plant were removed last year, but it continues to spread relentlessly and is already affecting other Spanish rivers.

The Mexican water lily (Nymphaea mexicana) is also spreading throughout Spain. Although it is propagating at a slower rate than the water hyacinth, once it has taken hold, the plant is even more difficult to eradicate. Whereas the water hyacinth is a rootless floating plant, the North American species roots securely in the riverbed. The bulbs remain anchored at the bottom and begin reproducing again once the plant is pulled out, making the process of removing it from waterways much more difficult.

Both species – the common water hyacinth and the Mexican water lily – and the giant reed are classified among the hundred most harmful invasive species by the IUCN. For this reason, cultivating and selling these plants has been prohibited in Spain and the rest of the EU since 2011. If we come across one of these plants along the banks of a river, reservoir or irrigation channel, we should report the sighting to park rangers. Under no circumstance should we collect a sample and bring it into contact with any other waterway.